The sensory qualities of artefacts help us understand where we come from and where we are going. Research from School of Classics and School of Computer Science demonstrates this with analogous projects: the former using tangible qualities of artefacts to engage learning, and the latter using digital tools to make artefacts accessible. As resources for education and cultural and creative arts dwindle, it is increasingly important for academics and practitioners to make existing assets available in a range of interactive ways.

Professor Rebecca Sweetman’s use of artefacts began when her team conducted a series of experiments (Through a Glass Darkly, TAGD) using the Bridges Collection of just under 200 physical artefacts dating from the Bronze Age to the Byzantine period. Her research showed that enabling people to interact with archaeological material through touch encouraged them to show greater consideration of the people who made and originally used the objects. Experiments, interestingly, also showed that touch led to a heightened ability to recall information about the object.

Building on Sweetman’s long-term interest of making archaeological material accessible to all, the TAGD team have taken their research into the community to show how engagement with material culture contributes to overall wellbeing:

Improving literacy in schools

Research by TAGD has shown that sensory engagement with artefacts encourages the creative thinking and confidence that promote reading and writing. The team organised literacy workshops at six primary schools, in which children were encouraged to explore objects in their own ways, both haptically and visually. This was seen to promote the children’s understanding of narrative, and motivated and empowered the children to develop their literacy further.

Sweetman’s work on engagement with material and literacy has involved over 1,000 children across a four-year period. Those involved benefited either directly or through professional development training and the creation of resources, such as loan boxes of replicas. The loan boxes provide lesson plans, props and replicas of archaeological artefacts to be used in the promotion of literacy. The feedback from primary school teachers involved in the work was extremely promising, with one remarking that they had “come away with practical steps to implement sensory elements in my practice”.

Improving learning & wellbeing of prisoners and dementia patients

TAGD has hosted multiple workshops with inmates across two prisons in Scotland to promote their education and wellbeing. 92% of the prisoners surveyed recorded that, as a result of the engagement, they felt better about themselves. In addition, the project has engaged with museums in Fife to promote haptic (sense of touch) and visual experience of unfamiliar artefacts as a beneficial practice in the care of early and middle stage dementia sufferers. This work was partly based upon an influential paper co-written by Sweetman, “Material Culture, Museums, and Memory”. Its development of haptic experiences with archaeological material for wellbeing and memory resulted in the paper being awarded the Chandler Screven Memorial Visitor Studies Outstanding Paper Award in 2021. The project’s latest phase began in early 2020 with the St Andrews Memory Café, a support group for patients and families, and hopes to resume soon.

Helping to preserve at-risk archaeological material through training

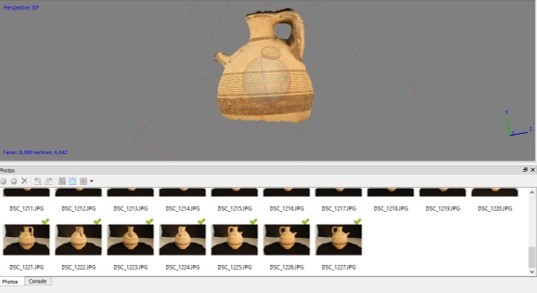

Sweetman’s work has included the conversion of over 130 physical objects from the Bridges Collection into online reconstructions. The virtual Bridges Collection allows visitors across the world to explore a cross-section of our global heritage and has reached over 9,000 people since its launch in 2017. Sweetman has complemented this work with a series of professional-facing events, including hands-on training workshops, individual meetings, and presentations given at museum and heritage sector conferences participants. As a result of TAGD’s training, and subsequent work in training others, the Assistant Professor of Strategy & Entrepreneurship is now collaborating with the newly launched Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, working in tandem with the US military to scan and preserve at-risk archaeological material.

Much like Sweetman, Dr Alan Miller has used artefacts to engage learning. Building on the research of the School of Computer Science in areas such as co-production, 3D technologies, and systems measurement and design, Miller has empowered museums and communities around the world to digitally engage with heritage sites and has brought the outside world into people’s homes during the Pandemic.

After developing a method to interact with virtual archaeology in 2010-2012, Miller and his team realized that it carried strong educational value, but that accessibility was restricted by technical limitations. This prompted them to develop digital systems that enhanced emergent 3D technologies which greatly expanded public engagement.

Digitally reconstructed historical sites and artefacts

Miller’s team, working with various museums and communities, co-produced the New Cultural Artefacts project, which digitally reconstructed historical sites including St Andrews Cathedral, which dominates the skyline of our small town despite being left to fall into ruin since the mid-16th Century. Artefacts including ceramics, stonework and even a Shetland pony harness have also been subject of digital reconstruction by the team, including 200 artefacts from museums across the Caribbean, Latin America, and Europe as part of the EU LAC Virtual Museum project. Miller’s further collaboration with museums across Scotland created 38 exhibitions, including venues in Edinburgh museums, the Scottish Parliament, the Helmsdale Highland Games, Shetland, and Perth.

Miller’s more recent work has involved developing techniques for digital restoration. Working with Mark Hall from Perth Museum, he has been creating a system which allows for an interactive representation of Pictish Stones. Carved between the 5th and 7th centuries, the stones are thought to have originally been painted in vivid colours made from mineral and plant pigments. However, the sculptures we are aware of today have been exposed to the elements for more than a thousand years, resulting in the colour being lost over time. Miller and Hall’s work allows us to imagine the Stones as they might have looked when the Picts originally carved and painted them, by choosing the colours of the individual decorations on a 3D model.

Developing museums’ capabilities in 3D and spherical media

Through numerous workshops helping participants to create digital heritage resources, museums across the world have been able to develop their own virtual resources. The first workshop in the Caribbean was held at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society (BMHS), a non-profit community museum established in 1933. Its directive is to collect, document and conserve Barbados’ heritage, and so Miller’s work had obvious potential to enhance their practice. More than 20 people participated in the workshop; among them were museum staff, university students and a youth group from a local church. Hosted over four days, the workshop’s project activities included a particular focus on the necessary photogrammetry and 3d processing skills to digitally replicate their own artefacts. The BMHS now has almost 30 artefacts digitally represented on the EU LAC Virtual Museum Website.

Following their training, the BMHS hosted their own training course, in which young people from the local area were taught 3d modelling through tutorials and hands-on sessions. This workshop resulted in the creation of six new models, and represented the embedding of Miller’s work within a new academic and social community. The participants expressed their eagerness to apply 3D modelling to a diverse range of fields, including geology and animation, demonstrating the potential of Miller’s research across a wide range of disciplines.

Miller and his team have also developed a Virtual Museum Infrastructure (VMI) which further supports installations, archives and exhibits, and has enabled digital heritage reconstructions and virtual tours to be incorporated into existing exhibitions. During the pandemic, Miller and his team have moved their training online, with workshops, social media events, roundtables and webinars covering topics such as digital galleries, virtual tours, interactive mapping, and virtual museums.

Connecting people with heritage during the Pandemic

Even though Covid-19 closed over 90% of the world’s museums, Miller’s work has allowed museums to remain connected to their visitors. Since March 2020, the team’s 44 “Museum at Home” programme of live online events included “Lords of the Isles” (Finlaggan Trust), “Coasts and Waters” (St Andrews Preservation Trust), and “Vikings Live” (Museum Nord), and reached nearly 400,000 people while giving new voices to archaeologists, curators, and historians.

These live events were complemented by Miller’s work developing virtual museum frameworks, which meant that museums such as the Barbados Museum have been able to continue sharing parts of their collections online, even while physical access has been limited or impossible. Furthermore, their work training museums has not stopped, but simply shifted online. Held on Zoom, and broadcast to an extended audience through social media, the workshops covered digital galleries, virtual tours, interactive mapping, and virtual museums. Live participation in Zoom for these workshops reached 800, while the total views for the workshop series overall were almost 50,000.

While the legacy of Miller and his team’s work would have been enough to enable significant cultural engagement during the pandemic by itself, their additional workshops during a time of unprecedented need empowered even more museums to reach out online during the lockdowns. Following the team’s series of webinars, led by the University and hosted by XpoNorth and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, 90% of questioned attendants reported feeling more comfortable working with digital technology. Many went on to host their own successful online events, including the West Highland Museum which held a live piping event for 7,400 viewers.

Whether engaged with physically or online, the power of tangible, novel and exciting artefacts has the power to reveal more about the lives of our ancestors, our neighbours and even ourselves. This power has been recognised across the University, and the diversity of research undertaken at St Andrews has allowed our understanding of the significance of artefacts to develop in several exciting directions. By taking a broader, interdisciplinary view, we can see the similarities in research projects that can seem entirely unrelated at first glance, and the profound value that they can bring to each other.