Alexia Petsalis-Diomidis from the School of Classics, is unlike most researchers I have met. Hair cut short, wearing a well-fitted suit with a dainty gold necklace and boots that could kill. Her office overlooks Castle Sands, with tall ceilings looming above us and bookshelves that reach them. Our voices bounce and echo off the walls as we speak. It takes only a minute of conversation to discover how warm, kind and open she is.

Petsalis-Diomidis is no stranger to laurels, having been shortlisted for the Times Higher Education 2021 Teaching Awards, received a Teaching Excellence award from the University in 2020, and won a McCall MacBain Foundation Outstanding Contribution to Teaching Excellence Award in 2019. Not only this, but she is also the author of two acclaimed books, “Drawing the Greek Vase” and “Truly Beyond Wonders: Aelius Aristides and the Cult of Asklepios” which I had the pleasure to read once the interview was over. There is something awe-inspiring about holding someone’s book in your hands. Years of research culminating in hundreds of pages, bound in sleek black hardback.

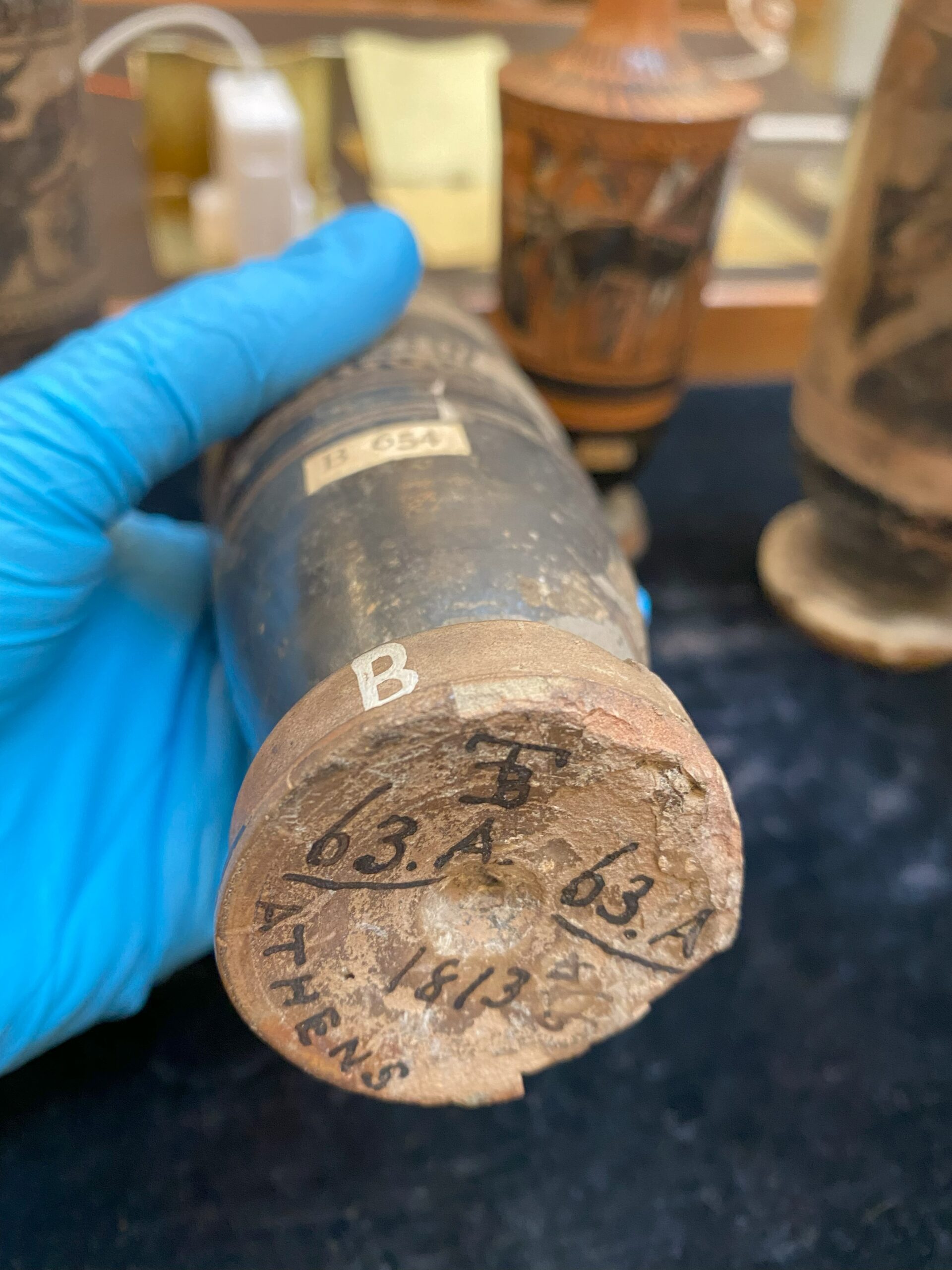

Petsalis-Diomidis’ current research revolves around the practices of collecting antiquities in the 18th and 19th century Ottoman Empire. Except, it’s not nearly as simple as that.

Recall the last time you locked your eyes on an object, and it was love at first sight. A postcard on the street. A vase at a flea market. Magnets from across the world that adorn your fridge. The first drawing you were gifted by a child. A love letter. We take these objects and infuse them with meaning, breathing life into them and holding them close to our hearts. These objects are extensions of our soul, tactile aspects of our being that hold our love, longing, dreams and ambitions.

When you visit a museum, you are often struck with the grandeur of antiquity. Looming portraits, magnificent sculpture but also small everyday objects like ink pots and tweezers – a rich mixture of artefacts. Many of these pieces were first part of collections in British homes and were a part of lived experiences long before they have been a part of national collections.

Petsalis-Diomidis’ research explores the relationships of people, both Ottoman and British, with classical objects which have become part of collections in Britain. The research places a specific emphasis on narratives that are regularly dismissed and marginalised, including those based on ethnicity and gender, and how children and individuals at different ages interacted with these pieces. Studying texts and documents related to collectors from Greek, Jewish and Albanian communities and of individuals from different social classes living in Britain, Petsalis-Diomidis has been able to compose an intimate image of domestic practices of collecting.

Petsalis-Diomidis has just edited a book on this subject and submitted it to the press – Travel And Classical Antiquities In Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Greece: Exploring Marginalised Perspectives (Routledge, forthcoming 2025). She is currently preparing another book which takes a deep dive into the story of a specific family in the early C19th. The Burgons were a Levantine and British family living in London, who had collected items from Asia Minor and Greece. She writes about the mother of the family, Margeurite de Cramer, hailing from Izmir, whose Ottoman clothing she has located in a museum in Chichester, and the way that she brought parts of her culture to the family home in Bloomsbury. Moreover, the children of the house would try to replicate the collections within the house by drawing them; this rich unpublished archive has been located in the Ashmolean Museum. These perspectives and complexities are often ignored and remain hidden from public view, being labelled as redundant.

She has explored other vignettes from the movements of antiquities including retracing scratch marks on the sculpted frieze from the temple of Bassae to a fox. Prior to its rediscovery, the frieze was buried within the temple ruins and had become part of the fox’s lair. Petsalis-Diomidis unearthed this story, reconnecting the narrative to the object and recontextualizing with other parts of the extended story by locating the earliest drawing of this temple drawn by Margeurite de Cramer. Focusing on the human side of material history, Petsalis-Diomidis hopes to bring to light the many interactions individuals have with objects, reinforcing complex narratives and presenting them in a respectful way, creating space for them and changing the traditional narrative dominated by aristocratic male collecting. Her work increases the preservation of diasporic traditions and opens routes for broader engagement with heritage today. She hopes that these narratives will help enhance the connection individuals feel when they visit museums, making them more relatable and grounding them in a reality that is familiar to all.